November 3, 2009

Film Journal International | Home

October 28, 2009

Film Journal International | Terminally romantic: George Clooney stars in Reitman's tale of frequent flyers

October 7, 2009

Film Journal International | New York, I Love You

September 23, 2009

Film Journal International | Toronto Fest takes aim at corporate America

July 16, 2009

Film Review | Flame and Citron

May 19, 2009

indieWIRE INTERVIEW | 'I'm Surprised When Anybody Likes It': Soderbergh On His 'Girlfriend Experience'

May 7, 2009

indieWIRE HONOR ROLL '09 |“I didn’t want ‘Y Tu Mama Tambien Two’”: Carlos Cuaron Talks “Cursi” and Cha Cha Cha

March 3, 2009

indieWIRE HONOR ROLL '09 | Self-Portraits and Biopics Dominate 14th Rendez Vous With French Cinema

February 6, 2009

indieWIRE HONOR ROLL '09 |Oscar ‘09: “Waltz With Bashir” Director Ari Folman

December 15, 2008

indieWIRE HONOR ROLL '08 | Engineering Simplicity: "The Class" Director Laurent Cantet

December 9, 2008

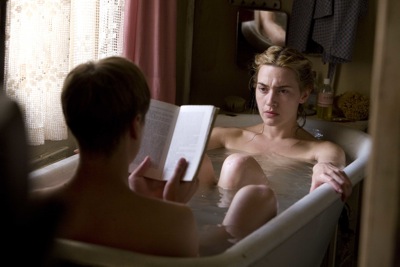

indieWIRE INTERVIEW | HONOR ROLL '08 | "He Didn't Bail, That's a Little Bit Unfair": "The Reader" Director Stephen Daldry

November 3, 2008

indieWIRE INTERVIEW | "I've Loved You So Long" Director Philippe Claudel

October 7, 2008

indieWIRE INTERVIEW | "Happy-Go-Lucky" Director Mike Leigh

September 26, 2008

indieWIRE INTERVIEW | "Lust, Caution" Director Ang Lee

September 11, 2008

Interview: Diane English on "The Women" | Film News | Film | IFC.com

July 25, 2008

indieWIRE INTERVIEW | "Brideshead Revisited" Director Julian Jarrold

June 20, 2007

indieWIRE INTERVIEW | "Lady Chatterley" Director Pascale Ferran

May 16, 2007

Blueberry Nights and the Crabwalk : Filmmaker Magazine: Blog

July 2, 2003

indieWIRE INTERVIEW | Francois Ozon on “Swimming Pool”: Fantasy, Reality, Creation

Home

In the anti-road movie Home, a happily eccentric family of five lives on the margin of a vast, unused highway east of nowhere. But when the road suddenly becomes opened to traffic, bombarding them with noise and exhaust, the clan refuses to relocate, hunkering down in the one place the fragile mother (Isabelle Huppert) can call home.

In the anti-road movie Home, a happily eccentric family of five lives on the margin of a vast, unused highway east of nowhere. But when the road suddenly becomes opened to traffic, bombarding them with noise and exhaust, the clan refuses to relocate, hunkering down in the one place the fragile mother (Isabelle Huppert) can call home.

In her assured big-screen feature debut, director Ursula Meier offers a provocative parable about individuals at war with development and the global economy. But the family's trials are inherently static, more a journey within than a cinematically riveting drama. Because of its eco-awareness and the ever-fascinating Huppert as a woman on the edge, the film should still pull in the art-house crowd.

Before the highway opens, it functions as the family's recreational space. They play roller hockey on the tarmac, its barrier functions as a shoe rack, and the older daughter, perpetually sunbathing in a bikini, amusingly treats it as her private beach. In this unorthodox but vital ménage, bath time is a shared event and on hot summer evenings the clan sprawls on a sofa in the garden watching TV. The kids go off to school and Dad (Olivier Gourmet) to work, but we never follow them; nor do we learn how they all ended up in such isolation.

The launch of traffic along the speed lanes makes for a forceful inciting incident, striking the family like an assault from another planet. In behavior that grows increasingly wacko, they attempt to go on with life as usual, dining al fresco over the racket of cars and rigs, while the older daughter continues to sunbathe at the road's edge, much to the delight of male motorists.

But the highway's deafening roar moves center stage, unraveling the fabric of family life. One member is mysteriously abducted; the middle daughter convinces her little brother that the fumes will stunt his growth; and every attempt to cross the road becomes a dance with death. Entombing themselves in a dark, airless space becomes the sole remedy.

The movie plays long. And once established, the folly of the family and their descent into semi-madness offers few surprises. Towards the end, their self-imposed claustrophobia becomes almost as punishing to the viewer as the characters.

Still, the film offers indelible visuals, such as Huppert larking about on the empty speed lanes; and, later, a giant traffic jam stalled before the family homestead, which scarily evokes a planet choking on its own abundance.

The role of an obsessed, intransigent woman is tailor-made for the ageless Huppert, and she's ably partnered by the great Gourmet. Tech credits are aces, the fluid camera of Agnès Godard becoming one with the family romps and pulling back for surreal long shots of Nowheresville (a stretch Meier found in Bulgaria.) Despite its flaws, by keying into fears about the spoilage of the planet, Home hits home.

back to the top

Terminally romantic: George Clooney stars in Reitman's tale of frequent flyer

“I fell in love with a character," says director Jason Reitman, explaining the genesis of his new Paramount film Up in the Air, debuting in theatres on Dec. 4. “Ryan Bingham fires people for a living, and characters who do unthinkable things for a living excite me.”

“I fell in love with a character," says director Jason Reitman, explaining the genesis of his new Paramount film Up in the Air, debuting in theatres on Dec. 4. “Ryan Bingham fires people for a living, and characters who do unthinkable things for a living excite me.”

Hanging his story on the bones of a tricky character is nothing new for Reitman. His debut feature, Thank You for Smoking, featured a shameless lobbyist for Big Tobacco, while sophomore effort Juno subverted expectations of how a pregnant teen would navigate her dilemma, becoming a megahit that grossed over $230 million worldwide.

Now Up in the Air—arguably the one winner out of the Toronto Film Festival and an Oscar front-runner—brings a new topicality to the mix. It's not only wickedly funny and peopled by recognizable characters, but with the pink-slipping of America, this tale of a corporate downsizer feels ripped from the morning headlines.

Reitman views his hatchet man Ryan as a current twist on the classic American salesman, selling dreams to folks devastated by the sudden loss of their careers, as he flies around the country. "Instead of going door-to-door, Ryan goes hub-to-hub," says the 31-year-old Reitman, who has striking good looks, the pallor of a Talmud scholar, and self-confidence to burn. "But if you're going to make a movie about a guy who fires people for a living,” Reitman adds, “he better be a darn charming actor. And there really isn't anyone better at that than George Clooney. The role was tailor-made made for him and it was probably one of the most exciting moments of my life when he finished reading it and said to me, 'Jason, it's great.'”

Living in airports, planes, and hotels with only a carry-on, Ryan also embodies a familiar male type: the commitment-phobe who avoids romantic baggage. When he picks up luscious business traveler Alex (Vera Farmiga) in a VIP lounge, he believes he's found a perfect match who shares his taste for no-strings affairs. (A priceless comic set-piece stages their mutual seduction by credit card and elite status perks.) But his airborne freedom gets threatened when smug B-school grad Natalie (Anna Kendrick) convinces Ryan's boss it's more efficient to dump workers via video conferencing. And when Ryan surprises himself (if not us) by falling for Alex, he discovers an unexpected need for attachment.

"This is my most original screenplay," says Reitman, who loosely adapted Walter Kirn's 2001 novel of the same name and shares script credit with Sheldon Turner. While keeping the book's central character and his occupation, he added such crucial figures as Alex, Ryan's love interest, as well as efficiency ace Natalie, Ryan's nemesis. And if Kirn's novel is "about a man losing himself, this film is about a man finding himself." Reitman also made the decidedly non-commercial choice to withhold a clear resolution. Instead, he points out, there's an epiphany. "It almost doesn't matter where Ryan goes from here. He has the information. He's undoubtedly changed. He can go back to the life he was living but not with the same perspective."

Reitman also considers Up in the Air his most personal film. Its screwball-style dialogue actually sounds like Reitman himself, who admits to being a "wise-ass" and likes whip-smart characters able to articulate their thoughts. The credit card scene was a snap to write, he says, because and he and his wife once flirted over the same thing. As in his previous work, Up in the Air also explores a compelling question. "In my first film, my questions were political. The second had to do with growing up. This one asks the biggest question of all: How do you spend your life—with people or alone? And as I made this movie, it confirmed the idea that I felt burning inside—that life is better with company, even if you believe you don't need anybody.”

As it happened, over the six years it took to write the screenplay, Reitman's own life changed. Like his anti-hero, he'd begun to consider airplanes, airports and hotels a virtual home. Then Reitman fell in love and married (writer/actress Michele Lee), and became a father. "In the course of writing the screenplay, Ryan Bingham the character and I discovered what was really important in life." When asked if there's been an Alex in his own life, Reitman replies, "I'm very happily married. And even if there had been, I don't think this would be the time to reveal it."

With its feel for the zeitgeist, Up in the Air also captures an America in thrall to its BlackBerry's, iPhones, texting and video chatting. These gizmos, Reitman asserts, convey a false sense of connection. "We don't talk any more. In fact, we're as disconnected as we've ever been. There's no sense of community or responsibility to be in a relationship. That's why so many of the conversations in this movie happen over video texting and phone calls"—and let's not forget a kiss-off e-mail that reads "Don't want to c u anymore."

Not one to tell people how they should live, Reitman admits to being equally addicted to texting and Twittering, adding, "I'm fortunate I get to make movies and work through some of these questions."

Up in the Air has left some viewers with questions of their own. Though reviews from Telluride and Toronto ranged from positive to rapturous, this critic took issue with a crucial twist in the third act, when the heroine displays the sort of emotional detachment that's usually the province of men. Reitman, however, sees no contradiction. "We're living in a very unique moment when women have been dealt a tricky hand. They're coming off the heels of the feminist movement and have more opportunity than ever before. But with that comes a lot of confusion about their role in society. Today there exist modern businesswomen exactly like my character, but who have not been portrayed onscreen. That's part of why I wrote this role. In a strange way, [Alex] is the man and Ryan is the woman in this relationship."

Even so, onscreen the character's 180-degree flip strains credibility. "That's good!" Reitman replies. "I don't want my characters to fit in easy boxes." All three of his films, he points out, contain a variety of characters who challenge the idea of how we should think of them. "That's what draws me to them. I like that it makes you a little uncomfortable when you see Alex acting the way she does. The idea is to catch you off-guard, to show you a different idea of the modern working woman. She's flirting with another life the way we presume men do all the time."

And what was it like to work with George Clooney? "He's about as good an actor as exists right now," says Reitman, lauding Clooney's ability to switch during a day's shooting from flip and charming to a man devastated by getting his world snatched away. "In this movie George has shown a level of vulnerability that most movie stars can't even touch. In the third act when he gets socked in the stomach, he never cries, you just look in his eyes and feel it."

Yet in making his ax-man so likeable, doesn't Reitman court the accusation that he's giving him and his odious job a free pass? One has only to compare similar corporate footmen in Michael Moore's Capitalism: A Love Story, who are portrayed as America's executioners. Further clouding the issue, Up in the Air includes painful footage of real people who were recently fired.

But Reitman doesn't see Up in the Air as a political film—even though when one character refuses to go on whacking workers, viewers feel tempted to applaud. "I actually don't think there's anything wrong with that job, just as I don’t think there's anything wrong with the job of head lobbyist for Big Tobacco," says the filmmaker. "The world needs all types. Sometimes people need to get fired—my wife recently was. Yes, it's heartbreaking that this many people are losing their jobs, but that doesn't make it wrong."

If Reitman, a Canadian, nails the zeitgeist in America, it's partly because he grew up and went to college here. From childhood on, he was something of a screen animal, using movie theatres with triple bills as daycare, as he puts it. "I've always been ahead of the curve, always started things very young."

An English major in college, he ran a desk-calendar business, using the money to make his first short film—then left school to make commercials. He's had the opportunity to be on sets his whole life, thanks to his director father, Ivan Reitman of Ghostbusters fame. As for the impeccable comic timing in Up in the Air, "I don't think you can learn it," Reitman says. "I think I was born with a sense of timing, tone, rhythm—important for comedy.”

Mostly, though, it's the countless hours working in the editing room—where "movies really come together and the magic is made"—that Reitman credits with teaching him the craft. "Watching [my father] be ruthless about his material made me ruthless about my own. I cut anything that doesn't work without a second thought, even if it's a great scene"—an approach much in evidence in Up in the Air, which is as lean and mean as Ryan's corporation. "I watch movies all the time and think, ‘This could go, and that’… I sometimes think movies have forgotten how to move."

Up in the Air not only moves, it's likely to take off big-time and land on the number-three spot in Reitman's trifecta of winners. The filmmaker attributes his success to date to the fact that his movies emerge from a deep inner wellspring. During the five years he tried to launch Thank You for Smoking, he declined offers to make bad movies which didn't speak to him. "It was very tempting to be on a set and get paid to direct movies. That was the dream. And to turn down those movies and wait it out was very hard."

Yet he considers those five years he waited the most important thing he's done for his career. "Because by starting with Smoking, it's allowed me to continue making movies that feel personal to me. I can't help but feel that if you try to make a personal movie every time, the probability that you'll make a good film is higher than if you just try to make a profitable one."

back to the top

Film Review: New York, I Love You

New York, I Love You continues the "Cities of Love" series that began with Paris Je t'Aime, far surpassing it. Though a few of the film's ten vignettes fail to coalesce within their allotted eight minutes and the inevitable final twist becomes predictable, most of these linked "shorts" succeed remarkably in nailing the serendipitous flavor of love, New York-style. At the same time, the ensemble of stories is knitted together by clever transitions or reappearing characters, forming an innovative multi-paneled portrait. The art-house crowd should cotton to the omnibus form and a tone ranging from street-smart to wistful.

New York, I Love You continues the "Cities of Love" series that began with Paris Je t'Aime, far surpassing it. Though a few of the film's ten vignettes fail to coalesce within their allotted eight minutes and the inevitable final twist becomes predictable, most of these linked "shorts" succeed remarkably in nailing the serendipitous flavor of love, New York-style. At the same time, the ensemble of stories is knitted together by clever transitions or reappearing characters, forming an innovative multi-paneled portrait. The art-house crowd should cotton to the omnibus form and a tone ranging from street-smart to wistful.

The helmers—an eclectic group ranging from Mira Nair to Yvan Attal to Brett Rattner—were bound by a few rules: They had only 24 hours to shoot, a week to edit, and needed to give the sense of a particular neighborhood. Perhaps these strictures have contributed to the film's breathless style, which adds to the sense of a city in overdrive. Though the filmmakers hail from all over, the Gotham conveyed here, curiously, is predominantly young, mainly south of 14th Street, cold and rainy, and populated with nervous types in leather itching to step outside for a smoke.

Two of the strongest stories come from French director Attal. As a romantic pitch-man, Ethan Hawke plies with dirty talk an attractive Asian woman (Maggie Q.) on the curb outside a Soho restaurant. But a wicked reversal suggests she might be better at his game than he is. A second New York moment again finds a man (Chris Cooper) and a woman (Robin Wright Penn) sucking in the nicotine, but this time the woman is hitting on the man. "You know what I always like about New York?" she muses, encapsulating the film's theme. "These little moments on the sidewalk, smoking and thinking about your life… Sometimes you meet someone you feel like you can talk to." On their return to the restaurant, their shared secret is revealed.

In a punchy if vulgar tale by Ratner, James Caan as a pharmacist suckers a young naif into taking his disabled daughter to the prom. Things are never what they seem in these stories, including, in this case, the daughter's agenda. Shekhar Kapur directs a haunting vignette suffused with sadness, with Julie Christie as a former diva installed in a New York hotel, where she's drawn to the lame Russian bellhop, Shia LaBeouf.

Along with the pungent sketches come a few duds: a Mira Nair-helmed encounter between Hassid Natalie Portman and a Jain diamond dealer (for this Portman needn't have shaved her head); Orlando Bloom as a frantic musician on deadline somewhere grungy on the Upper West Side; and Andy Garcia matching wits with Hayden Christensen in a flaccid love triangle. But any misses are redeemed by a touching and humorous final vignette by Joshua Marston, with Eli Wallach and Cloris Leachman as an aged couple making their own style of love in a town that belongs to the young.

Most original of all, New York opens a romantic window into the city via a sort of filmmakers' cooperative. The vignettes are tied together into a single feature through a "recurrent character," a videographer who interacts with the other characters. And transitional elements—choreographed by 11th director Randy Balsmeyer—move the viewer from one world to another, uniting all these intimate stories into a single shimmering fabric.

back to the top

Toronto Fest takes aim at corporate America

The 2009 Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) was marked by a smackdown of American corporate culture. Usually, especially in Cannes, we could depend on Lars Von Trier and other European auteurs to do the job. But this time round, it was American filmmakers who blasted inequities and corruption in the executive suite. At the same time, these reports on the zeitgeist couldn't have been timelier and doubled as razor-sharp entertainments.

The 2009 Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) was marked by a smackdown of American corporate culture. Usually, especially in Cannes, we could depend on Lars Von Trier and other European auteurs to do the job. But this time round, it was American filmmakers who blasted inequities and corruption in the executive suite. At the same time, these reports on the zeitgeist couldn't have been timelier and doubled as razor-sharp entertainments.

Also notable this year was the slew of accomplished films from women directors. Already, both An Education by Lone Scherfig and Bright Star from Jane Campion have collected buzz as awards-season fodder and will doubtless run up against The Hurt Locker from Kathryn Bigelow.

If TIFF's 200-plus lineup produced no breakout Slumdog Millionaire, the consensus had it that Jason Reitman's Up in the Air, the tale of a corporate hatchet man played by George Clooney, emerged as an awards-season front-runner. Unlike previous editions of TIFF, which could count a cluster of candidates, Reitman's film stood alone. Generally, buying was sluggish, though mid-fest the Weinsteins snapped up for $2.5 million Tom Ford's splendid first feature and Colin Firth starrer A Single Man.

Chief among the cluster of strong films that critique the U.S. was, of course, Michael Moore's much-anticipated Capitalism: A Love Story. Moore does a bang-up job of taming his vast, diffuse topic into a broadside at once instructive, enraging and entertaining. Essentially, he sets out to demystify a system rigged to permit Wall Street titans and bankers to rake in the shekels while less fortunate citizens spiral into poverty from unemployment, get ousted from foreclosed homes, and die from lack of health care. Singled out for attack are Goldman Sachs and other key players in a shadow government that calls the shots in Washington.

Reprising his signature set-pieces, Moore shambles up to security guards at corporate strongholds to request face time with the CEO, and surrounds the New York Stock Exchange with crime-scene yellow tape. Predictably, some critics taxed Moore with oversimplifying. I agree—but Moore adopts this tactic in the hopes of expanding his reach beyond the elites. And considering that even a Harvard prof interviewed in the film pfumphered around when asked to define "derivatives," maybe simpler is to the good.

First-time director Derrick Borte gave us The Joneses—as in "keeping up with"—which lobs a grenade at American-style consumerism. Toplined by Demi Moore, David Duchovny and Amber Heard, the film follows the handsome Joneses as they move into their new McMansion in an affluent gated community. But it quickly becomes apparent that this foursome is a faux family positioned by a company to whip up the acquisitive instinct of their neighbors and inspire them to go on a buying frenzy. As Duchovny’s character puts it, "Whoever dies with the most toys wins." Despite a feel-good denouement you can spot 15 minutes in, the film offers a mordant morality tale about the American Dream turned rancid.

Steven Soderbergh’s recently opened The Informant! could stand as an enlarged detail from from the broad overview presented by Moore's Capitalism. A stealth social critic, Soderbergh continues to explore the values of America's corporate culture, conveyed in his films as no more a choice than the air we breathe. His Girlfriend Experience, for example, proposed that everything's up for sale and even intimacy can be purchased like socks.

In The Informant!, based on the book by Kurt Eichenwald, a chubbed-up Matt Damon plays a young exec at agribusiness giant Archer Daniels Midland, who exposes his employer's price-fixing scheme. Avoiding the earnestness of, say, Michael Mann in The Insider, Soderbergh sidewinds his attack on corporate abuse using Marvin Hamlisch's vaudeville-like score, complete with kazoo, and his anti-hero's oddball voiceover. The film's murky-yellow palette reveals as much about this milieu as dialogue or plot.

Canadian Jason Reitman, who grew up and attended college in the U.S., might be considered an honorary Yank. His lavishly praised Up in the Air, loosely adapted from American Walter's Kirn's novel—and following on Thank You for Smoking and Juno—marks a winning three-for-three for Reitman. George Clooney plays a coolly detached executive who makes a living flying from hub to hub and firing people. He meets his romantic double in fellow road warrior Vera Farmiga, who also avoids entanglements and gets off on elite status, and his nemesis in an arrogant B-school grad who prefers axing people via video. The mix of screwball comedy, hot-button issues and the Clooney charm offensive should resonate at the box office.

Other American films touch on corporate rot—or Yankee cluelessness—in less direct ways. In Soliltary Man by Brian Koppelman and David Levien, Michael Douglas delivers a brave turn as an aging, once-successful exec in freefall. In the film's morally bankrupt world, Douglas' compulsive womanizing is presented as a compensation for his loss of status. Constructed like a thriller, The Art of the Steal by Don Argott (just picked up for distribution) is an exposé about a power grab by charities and Philadelphia pols and financiers to control and relocate the multi-billion-dollar Barnes collection of art. The film's little guys battling to protect Barnes' bequest could have come from the playbook of Michael Moore. Finally, even The Invention of Lying by Ricky Gervais presents the citizens of Anytown U.S.A. as gullible yahoos.

As mentioned, this year's TIFF was also marked by a strong showing from female filmmakers. Regrettably, I missed Drew Barrymore's Whip It, which sounds like a hoot, The Vintner's Luck by Niki Caro, and Rebecca Miller's The Private Lives of Pippa Lee, featuring a lauded turn by Robin Wright Penn. I did catch the standout Bright Star from Jane Campion, which re-imagines the romance of poet John Keats (Ben Whishaw) and girl next-door Fanny Brawne (Abby Cornish).

Though a period piece, Bright Star bears no trace of Merchant Ivory or “Masterpiece Theatre.” Taking great formal risks, Campion reinvents the biopic, replacing straight narrative with scenes that play like stanzas in a poem, separated by fades to black. The film charts Fanny's budding intimacy with the penniless Keats, which is opposed by a society that expected women to marry well. From a flirtatious minx, as Keats calls her, Fanny evolves into a woman whose passion for the poet embraces his work. To judge by all the figures bathed from the left in light, Campion has looked at a lot of Vermeer. In fact, this exquisite film is besotted with light, conveying an ethereal passion less through story than degrees of radiance.

Lone Scherfig's An Education, a launch for new It girl Carey Mulligan, arrived in Toronto fresh from accolades in Telluride. Set in early-’60s London, it features a bright teen gunning for a spot at Oxford, who gets seduced away from her goal by older sophisticate Peter Sarsgaard. Though Nick Hornby's script expertly combines a coming-of-ager with a culture on the cusp of change, I found Sarsgaard's older man a bit smarmy and distasteful.

Vision by German feminist auteur Margarethe von Trotta will doubtless not find distribution here. A pity, since its portrayal of a medieval German nun starring the sublime Barbara Sukowa showcases a proto-feminist who should resonate with women across the globe.

Similarly, Lourdes by Austrian auteur Jessica Hausner (Hotel) might be too austere to attract a stateside distributor. It follows a paralyzed woman played by Sylvie Testud to the famed Christian hot spot where the ill flock seeking a cure. Elina Lowensohn indelibly plays an otherworldly nun conducting the pilgrims through the shrine. The film takes no religious stance, preferring simply to observe the "miracle" that mysteriously heals one pilgrim who, ironically, has little faith. Haunting and stately—and much admired in Venice—Lourdes is the work of a richly gifted filmmaker.

As always, this year's lineup included films that landed somewhere between between watchable and misfire. In fact, you could gauge audience judgment when more people in your row were looking at their BlackBerry than at the screen. Falling among the blunders was Tim Blake Nelson's Leaves of Grass, with the excellent Edward Norton in the roles of identical twins, one an Ivy League professor, the other a lowlife yokel mired in the ’60s. Ostensibly an attempt to explore the power of fraternity, the film ricochets between farce and melodrama like a car stripped of gears.

Into the category of guilty pleasure falls Oliver Parker's Dorian Gray, an adaptation of Oscar Wilde's famous novel about a gorgeous innocent who sells his soul to retain his youth and beauty. Meanwhile, his portrait, famously, reveals his true inner rot. Toplined by Ben Barnes and Colin Firth, the film works Gothic horror tropes to often enjoyable effect, yet fails to tease out the homosexual subtext of this Victorian tale about a love that dare not speaks its name. But, oh, those great rugs in Dorian's mansion.

When two fine dirty minds combine forces—think director Atom Egoyan and scripter Erin Cressida Wilson—you're apt to get a sizzler like Chloe. Julianne Moore plays a long-married woman who suspects her professor husband (Liam Neeson) of having an affair. After she hires a sultry escort (bug-eyed babe du jour Amanda Seyfried) to seduce her husband and test his loyalty, the relationship between the two women gets hot and heavy. Egoyan's psychosexual thriller uncorks a wicked twist, but derails when it lapses into Fatal Attraction territory. You come away from this wondering: Is there anything gutsy Julianne Moore won't do?

Finally, TIFF usually delivers one film that soars above the rest. In this edition it was designer Tom Ford's debut feature A Single Man. Mid-fest, its star Colin Firth took best actor in Venice, creating frenzy in the halls of the Manulife Center, home to most of TIFF's theatres.

In this adaptation from a late novel by Christopher Isherwood set in 1962 California, Firth plays a gay college professor mourning the death in a car accident of his longtime lover (Matthew Goode). Far from reconciling with his loss, Geroge is methodically staging a suicide. But fellow Brit and best gal pal Julianne Moore keeps him tethered to life, along with a dishy male student whose eyes express more than a search for a mentor. Not only is the period detail spot-on, but Ford ties the convergence of Cold War fear-mongering to a gay man's isolation in 1960. I've always thought Colin Firth a superb thesp, yet never suspected in him the incandescence and depth he brings to the title character, using his voice like a Stradivarius.

back to the top

‘Y Tu Mama Tambien Two’”: Carlos Cuaron Talks “Cursi” and Cha Cha Cha

The making of “Rudo y Cursi” was like a big fat family reunion. This clan, though, is linked by creative affinities as well as blood ties. And unlike many families that spring to mind, the “Rudo” collective is about mutual supportiveness and the celebration of brotherhood. Hard to sort out all the team’s affiliations, but here goes: “Rudo”‘s director/writer Carlos Cuaron is the younger brother of Alfonso Cuaron, director of “Y Tu Mama Tambien,” for which Carlos wrote the script. The film’s producers - bro Alfonso, Gullermo del Toro and Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu - are long-time collaborators working on their new production company, Cha Cha Cha with “Rudo.”

If you’re still with me: the film’s two stars, Diego Luna and Gael Garcia Bernal - reunited on screen for the first time since “Mama” - have been buddies since childhood and run their own film company. Says Luna, “we’re in it together for the journey.”

Fittingly, “Rudo,” Cuaron’s first feature, explores the dynamics of brotherhood - an “emotional autobiography,” he calls it. Luna and Garcia Bernal play Rudo and Cursi, squabbling siblings who work on a banana plantation. Rudo (Spanish slang for tough) dreams of becoming a soccer star, while Cursi (or corny/cheesy), wants to be a pop singer; and both long to build their beleaguered mom a grand house on the beach. After soccer scout Batuta (Argentine comedian Guillermo Francella) spots their moves in a local game, the brothers head off to Mexico City to play the big leagues.

But success proves fickle and eventually the pair faces off in a climactic penalty kick, shot like a Sergio Leone Western. Though soccer is the context, “Rudo” uses the sport as a filter through which to tell a story of rivaly, aborted dreams, and the primacy of family. And the film’s comic elan is infused with dark social commentary. The rough-and-tumble rapport of Garcia Bernal and Luna bounces off the screen in the manner that made “Mama” such a joy; and Cuaron has fun with a cheesy music video of Garcia Bernal singing badly.

Beneath the horseplay “Rudo” implies that soccer and singing, the ticket out for Mexico’s slumdogs, work for only a tiny fraction. And the closing images of a wedding are shadowed by the narco money behind it and the installation of a drug lord as the new surrogate father. indieWIRE recently caught up with Carlos Cuaron when he was in town with his two delightful stars to promote the film.

indieWIRE: What originally inspired this film?

Carlos Cuaron: I first wanted to make a mockumentary about a soccer player who came from a humble background, who made it big, and when he was at the peak of his success mysteriously disappeared. When I told this idea to Gael and Diego separately, they both wanted to be that guy. But I had only one character, and I realized at that point that I wanted to work with both of them. So I told them it was going to be a sibling rivalry story. I told Gael I wanted him to play Cursi and Diego to play Rudo. And their first reaction was no, they wanted to play the other guy. And I told them that I didn’t want to repeat myself and make “Y Tu Mama Tambien #2” and I wanted to cast them against type. They got it immediately and started to throw ideas at me. They’re very proactive.

iW: How did you get the project off the ground?

CC: I pitched the idea to my brother and he said great, when you have a screenplay finished, I’ll produce it. And what do you think of Alejandro and Guillermo producing it? They had just formed Cha Cha Cha. It was a surprise to me but I was honored.

iW: Does the bond between Rudo and Cursi parallel yours with your brother?

CC: Oh, besides the fact that we’re both idiots? Look, brotherhood is universal and the way you relate to your siblnig is probably very close to the way I react to mine. You can have an argument and hate him and ten minutes later it’s fine. And then sometimes it’s 25 years later and it’s like, ‘Yeah, I hate you.’ That’s what brotherhood is all about. That’s what was so nice about Obama’s gesture in Tobago. Instead of making war, which is what Bush used to do, he said. ‘yeah, we don’t have to agree, but we can be friends.’

iW: With “Rudo” as the first film up from Cha Cha Cha, did it add to the pressure?

CC: I was too stupid, like a donkey following the carrot, I just wanted to make my movie. They gave me complete freedom, but were also very demanding because that’s the way they are, and that’s the way I am. They send me their scripts, we get into each other’s cutting room - so we sort of officialized the relationship with this production company. They gave me great feedback all the way.

iW: It seems you almost go out of your way not to show soccer in the movie. Why?

CC: Because it’s not a soccer movie. It’s a movie about brotherhood. Actually, I didn’t need to show soccer. If you like the game, there’s no better place than the stadium, or TV with all its cameras and slo-mo. There’s no way you can shoot that in a movie. What I show is the human emotion reacting to what’s on the field or the sportscasters narrating the game. And I only go into the field at the climactic moments of the rivalry between the two guys, because that’s what’s important.

Also, soccer is a sport that is not easy to dramatize. Baseball has pauses; between each pitch there’s something at stake. The same with American football, or boxing, the most dramatic sport. But with soccer the ball never stops, there’s no pause, no drama. The only real dramatic moment is the penalty kick. It becomes a Western duel, two guys facing each other, with destiny, a metaphorical death at stake.

iW: Did you have to teach your main actors soccer?

CC: Yes, they were such bad players. They trained for about two or three months. I wanted them to look real with the ball and the postures - also to get fit. Gael had to run a lot and the legs won’t react if you don’t have the physical capacity. I think they had a lot of fun, especially Gael. But Diego hates to be a goal keeper, so he suffered. Gael also took singing lesssons so he could control his voice enough to sing badly. He sings better in reality than the way he sings on screen.

iW: What’s it like to work with Gael and Diego?

CC: Their complicity and chemistry is something you can’t get with rehearsals. It really helps that they know each other and that we know each other so well. We know our strengths and weaknesses and each other’s moods. We could vent because that’s what you do with your siblings. But they were very respectful and knew that I had to fulfill my vision - and we shared that vision.

iW: Despite its high spirits, I came away feeling this was quite a dark movie.

C: Well, their sister marries a drug lord. My intention with the film was to create a social portrait of my country. Not just the class issues, but also show that the drug guys have penetrated every single thing in Mexico. In fact they have become perhaps the most solid institution in Mexico. The drug lords provide for the communities, build roads, churches, schools. What’s usual and sad now is that the drug world is recruiting young people - they have few other opportunities. The Mexican dream has become a nightmare. The other thing you can say is that drug dealers are bad and they kill people, but at the same time you have one million people working for them and they provide for one million families and that’s a lot.

iW: You’ve also described “Rudo"as a wolf hidden in a sheep’s skin. What’s the nature of the wolf? Dashed hopes?

CC: To me it’s reality. In reality a few people are champions, a very few get to be president. We’re used to Hollywood movies that say, oh yeah, that’s possible, but that’s a lie. And I like honesty above all. Life gives you beautiful moments and then next thing it’s totally dark and shitty and you want to kill yourself. The movie is about how life treats us. There’s no pure black and white, but all the tinges of gray.

iW: In fact, all through the film there’s the nagging sense the brothers are going to derail…

CC: That’s because they don’t have a platform - education. They can’t be successful in the materialistic sense. But I actually think these two guys are really succesful as human beings. They don’t succeed as soccer players because they have these flaws and screwed it up. But as brothers they do succeed. They come to terms with each other and they know that they have each other. In the most human way they are winners.

iW: The collective “family” that created “Rudo” is pretty remarkable. Is there something about your collaboration that’s particular to the Mexican culture?

CC: Probably. I think it has to do with the way we regard family. We can be scattered around the world and we can still be very close and know what’s happening with everyone. When you create strong friendships you become family. Alfonso is my brother, but the others have become my brothers in the process of making the movie.

iW: It sounds a little too good to be true.

CC: It sounds corny.

iW: People are by nature rivalrous.

CC: We admire each other and we don’t fee bad about saying that. Alfonso can come to me and say, ‘Great screenplay!’ and really mean it. But for the people outside our famly, yeah, there’s some jealousy.

iW: Do you fear having to compete with the big success of “Y Tu Mama Tambien?”

CC: I have to live with that, yes. But I don’t have to compete with anyone but myself. I don’t care about being better than the other guy, but can I be better than I was the day before? That kind of competition I do care about. Yet the comparisons between “Y Tu Mama” and “Rudo” are inevitable because it’s the same creative team. They are like sibling movies.

“Rudo” is somehow the continuation of the work that we started with “Mama.” That’s perfectly natural. There are many similarities and many differences. And the good news is that the comparison is with something I believe is a good movie. Same with my brother - there will always be comparisons between us, yeah! I’ve lived my life with that. I don’t have a problem. Do I feel bad? No! If he was a shitty filmmaker then I would feel bad. But he’s a great director so if I get compared to him I just feel that it’s good news.

iW: But sometimes one suffers by comparison.

CC: I don’t. Because I know that he is really talented and I’m grateful for what he has taught me. And he’s also very grateful for what I have given him… I will never be able to make a film like “Children of Men,” it’s amazing, one of my favorties. I will not attempt such a film - I don’t have the talent and I don’t care. I have my own path and we share a path together too. And we love that, we do not question that, we just do it.

iW: How did you move into filmmaking in the first place?

CC: When I was fourteen I decided I wanted to be a writer. So when Alfonso needed someone to write his scripts, he said, ‘hey you, you want to write? Come, help me.’ So that’s how we started to work together - I was nineteen back then. I decided to start directing in the mid ‘90s. I had lunch with Guillermo and Alfonso and I was depressed and Guillermo said, ‘What’s wrong with you?’ I said I’ve written all these scripts and they don’t get produced, it’s like giving birth to dead babies, and he said, ‘well why don’t you direct them?’ And I thought, ‘yeah, he’s right.’ The thought had never crossed my mind because I’d wanted to be a writer and that was that. So I started writing scripts for short films and I did eight.

iW: Why has it taken you till age forty-two to make your first feature?

CC: I tried to make my first feature ten years ago, a completely different project. That project collapsed. At the same time a project of Alfonso’s collapsed And that’s how we ended up making “Mama.” I also discovered that I was not ready to direct a feature. All these years helped me a lot. I’ve done eight shorts. And it helped to work with Alfonso. That was school for me. I didn’t do film school, I was an English major.

iW: Would you like to do a film in Hollywood or an English-language film?

CC: I’m open to everything. If I get a good offer for a project I can connect with, I’ll do it. I would make a Hollywood movie as I would make an Argentinian movie or a Japanese movie.

iW: Is it important to you to write your own script?

CC: It’s important for me to connect with the material and feel it is close to me. If it’s not, it’s a waste of time because filmmaking is really tough and takes a lot of time and life is short. I’d rather be doing somethig else.

iW: What’s the quality most crucial for a director? I understand getting a vision to the page. But how do you put one on a screen?

CC: As a director you have to put yourself at the service of the project and not the other way around. Many directors have the projects at their service and that’s egotistical and narcissistic. If you put yourself at the service of your project, then all your team is going to die for it. Because they’ll see your attitude. They won’t die for you personally, but they will die for your project and that’s what you want.

back to the top

Flame and Citron -- Film Review

Bottom Line: A bold, riveting tale of wartime resistance borrowing the form of a noir thriller.

Bottom Line: A bold, riveting tale of wartime resistance borrowing the form of a noir thriller.

NEW YORK -- From the opening black-and-white footage of Nazis invading Copenhagen, "Flame and Citron" draws you into its doom-laden atmosphere and keeps ratcheting up the tension. This searing, stylish account of World War II heroism from Denmark's Ole Christian Madsen avoids period realism, conveying the story of two heroes of the Danish resistance as a noir thriller, complete with shadowy alleys, double-crosses galore and the requisite femme fatale.

Beneath its stylized surface, "Flame" is also a provocative film of ideas, exploring the notion of heroism. Although based on true events, it unspools like a fever dream, circling back to the hero's opening voiceover, which at the end takes on new poignancy.

This icy portrait of two assassins shooting Nazis point-blank offers no Hollywood-style uplift to mollify mainstream viewers. But "Flame" should pull in a niche group of World War II connoisseurs and will delight art-house and fest audiences with its innovative mix of drama and history filtered through genre. The film opens in New York on July 31, then in L.A. and a other markets August 14.

It's 1944 and Copenhagen is occupied by Nazi forces. Two resistance fighters with the noms de guerre of Flame (Thure Lindhardt) and Citron (Mads Mikkelsen) work undercover for the Holger Danske Group, assassinating Danish turncoats. They also itch to off the German invaders, in particular the silver-tongued Hoffman, head of the Gestapo in Denmark. Flame and Citron take orders from the well-fixed Aksel Winther (Peter Mygind), who in turn receives orders from London.

Known for his red hair and fearlessness, Flame, barely 20 and the younger of the duo, has become notorious throughout Copenhagen and carries an inflating price on his head. He acquires Ketty (Stine Stengade), a femme fatale in a Veronica Lake blonde wig, who works for the underground as a courier.

Following the loss of two comrades in the cell, it becomes apparent there's an informer in their midst. Now all loyalties appear murky. To the film's credit, it captures the confusion among the renegades -- call it the fog of resistance -- keeping the viewer as off-balance as the fighters.

Winther, it turns out, may be using his position as a front to protect financial interests tied to the Germans. Meanwhile, Ketty, though seemingly in love with Flame, may be a double -- or triple -- agent. Disillusioned with their self-seeking superiors, Flame and Citron become resistance "outlaws," pursuing their own vendetta to its inevitable bloody denouement.

It helps that the vendetta is carried out by two gorgeous, charismatic actors. Lindhardt, with his orange shock and milky skin, makes a riveting screen presence. Despite the film of cold sweat over his grizzled face and unflattering glasses, Mikkelsen's sculpted, exotic beauty pierces through.

The Occupation literally makes Citron sick to his stomach, leaving him with no choice but to fight it. Though more wed to battle than family life, he also loves, in his fashion, his wife and child. In a wrenching scene, he clumsily comes on to his wife, his need for her palpable, but she knows that at heart he's a rootless wanderer.

Flame, from a privileged background, developed his hatred of Fascists after witnessing anti-Semitism in Germany. Through Flame the filmmaker looks deep into the character of a hero, suggesting that he loses some of his humanity to the Cause and risks resembling the enemy he fights.

In a telling face-off, Flame visits his hotelier father, owner of the mountain retreat favored by Nazi bigwigs, who simply wants to get by. The film indirectly challenges viewers to ask what they might do in a like situation.

For "Flame's" bravura style, credit goes to below-the-line contributors. Cinematographer Jorgen Johansson favors overhead shots of figures in fedoras and stormtrooper uniforms fanning out or closing in like pawns directed by a higher force. Production designer Jette Lehmann has contrived a palette of gunmetal greys and livid whites daubed with red velvet, especially striking in the barny backrooms of cafes.

In its tough-mindedness "Flame" owes much to Jean-Pierre Melville's "Army of Shadows." Avoiding the docu-style string of anecdotes of many fact-based films, it offers the shapeliness and irony of classic drama. For beneath his stony exterior, it's Flame's romantic soul that will prove his worst enemy. This masterful film is at once a portrait of wartime heroism and a poignant journey into a boy's secret heart.

back to the top

“I’m Surprised When Anybody Likes It”: Soderbergh On His “Girlfriend Experience”

“The Girlfriend Experience,” a riveting provocation from Steven Soderbergh, is so organic and of a piece - it contains nothing extraneous, nothing that doesn’t serve its central concern. Take, for example, the voice of a ritzy call girl named Chelsea, played by porn starlet Sasha Grey. Chelsea’s flat-line monotone mirrors the film’s proposition that in the consumer society everything exists on the same plane and can be reduced to a commercial transaction, whether it’s bonds, sportswear, or sex. Or, in the case of Chelsea, a combo of sex plus intimacy for two grand an hour that’s called a “girlfriend experience.” For those who don’t get out much, this rentable relationship is available from a kind of one-stop hooker known as a Girlfriend Escort or GFE.

“The Girlfriend Experience,” a riveting provocation from Steven Soderbergh, is so organic and of a piece - it contains nothing extraneous, nothing that doesn’t serve its central concern. Take, for example, the voice of a ritzy call girl named Chelsea, played by porn starlet Sasha Grey. Chelsea’s flat-line monotone mirrors the film’s proposition that in the consumer society everything exists on the same plane and can be reduced to a commercial transaction, whether it’s bonds, sportswear, or sex. Or, in the case of Chelsea, a combo of sex plus intimacy for two grand an hour that’s called a “girlfriend experience.” For those who don’t get out much, this rentable relationship is available from a kind of one-stop hooker known as a Girlfriend Escort or GFE.

The chameleonic Soderbergh has long mixed studio entertainments with art house gambits that can range in scope from epic to chamber pieces. Following on the two-parter “Che,” the 77-minute “Girlfriend”—released on video-on-demand three weeks before it’s set to hit theaters this Friday - focusses for six days on Chelsea during the recent presidential campaign, Palin and McCain on the tube and everyone obsessed with the tanking economy. Lusciously lensed on HD, the camera trails Chelsea to swanky downtown haunts where she meets her johns - no graphic sex but lotsa restaurant porn - and the posh apartment she shares with devoted boyfriend Chris (Chris Santos), a personal trainer hoping to launch a sports apparel line. We see her on a date with a client discussing “Man on Wire,” while another offers her financial advice and she inquires after his family. In true American go-getter spirit, she spends downtime developing a promotional website and diversifying her assets. At some point in the shuffled time scheme Chelsea falls for a married West Coast screenwriter named David (David Levien, one of the film’s writers) and her desire for a weekend tryst with him becomes a deal-breaker for Chris.

All this is conveyed in a fragmented form reminiscent of the early 60’s Godard of “Vivre Sa Vie.” “Girlfriend” also scrambles time in a manner that sometimes challenges the viewer’s ability to tease out the story. For instance one repeating - and hilarious - scene of hedge-funders on a private jet to Vegas could or could not be the film’s “true” ending. And “Girlfriend” continually doubles on itself to comment on narrative and filmmaking. Throughout, Chelsea is being interviewed for a piece on a call girl in a committed relationship by actual “New York” writer Mark Jacobson. A self-styled Erotic Connoisseur (film critic Glenn Kenny, creepily credible) barters the promise of a rave review on his web site for a free sample of the wares. And the poised, if waxen Chelsea is herself a scribbler, narrating in voiceover which designer duds she wore on each date, what was discussed, and her clients’ niche desires (did I spot a dude in diapers?). One john even suggests she make a movie to build her brand.

IndieWIRE recently met with Steven Soderbergh and discussed his film’s view of late capitalist society, scrambled versus linear time, and the novel just published by his wife Jules Asner.

indieWIRE: I loved this movie.

Steven Soderbergh: Really! I’m surprised.

IW: Why?

SS: Well, because it’s very polarizing. I’m surprised when anybody likes it. It’s one of those things people either really like or really just want to get away from.

IW: What’s not to like?

SS: A lot of it’s expectations. What do you want out of a movie to begin with. And then, what do you want the form to take. What kind of performances are you interested in. How do you want the stories to be told. I did an audience test on “Out of Sight.” And some guy in the focus group said, I just want to say I hate stories that are told like this, where they don’t go in a straight line - and that became a lightning rod and turned the thing into a free-for-all.

IW: Speaking of non linear, I have questions about what happened. David, the guy she’s interested in - well, we see the scene of him standing her up towards the middle of the film.

SS: That’s right. And the last scene we see of the two of them together was actually the first time they met, when he goes to her hotel room for the first time..

IW: And that comes after he stands her up. Now why would you do that?

SS: The scene of them meeting for the first time has a different weight if you know he’s going to betray her. It has another layer of poignancy to me because you see her beginning to be engaged by this guy who’s going to, like, emotionally betray her. I just like the idea of that being the last scene [which is the first scene chronologically].

IW: The film continually reflects its own process. Who is Chelsea narrating to in her voice over?

SS: This is something we learned in talking to real escorts. They keep journals about everything. Technical things, so they don’t wear the same clothes. They’re current on whatever issues their clients are interested in. It’s like their homework. All of them told me this is what they do.

IW: Any particular reason you gravitated toward this post-modern self-reflecting structure?

SS: I was trying to just give a sense of what her interior life is like. That her interior life is not linear. The idea of the linear narrative is very much a construct. When you’re walking down the street you’re aware of the fact that you’re walking down the street; you’re thinking about what you did before you left this building; and you’re thinking about going from this building to your apartment. Your mind is moving in these three realms. And depending on what’s going on in front of you, you’re shifting the emphasis of each as you walk along. I"m trying to recreate that sense of how our minds are constantly sifting and filtering our experiences and we’re trying to connect stuff. Because we’re trying to organize this chaos and convince ourselves that there’s some sort of narrative here and we’re not going insane. And film can recreate that sensation almost better than any other art form.

IW: Better than writing.

SS: Yes, because you don’t have to describe things, you can show them. It can be very elegant if you do it well. It also depends on what your goal is with the piece. I’m less interested in the nuts and bolts of the narrative than in you feeling what it’s like to be Chelsea for a week. The impulse of the film was more driven by: what’s it like to be this person for six days? than: I want to tell a story that goes from A to B to C. It’s just an impression of her.

back to the top

Oscar ‘09: “Waltz With Bashir” Director Ari Folman

EDITOR’S NOTE: Over the two weeks leading up to Oscar, indieWIRE will be republishing a series of interviews and profiles on the nominees for the 81st Academy Awards.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Over the two weeks leading up to Oscar, indieWIRE will be republishing a series of interviews and profiles on the nominees for the 81st Academy Awards.

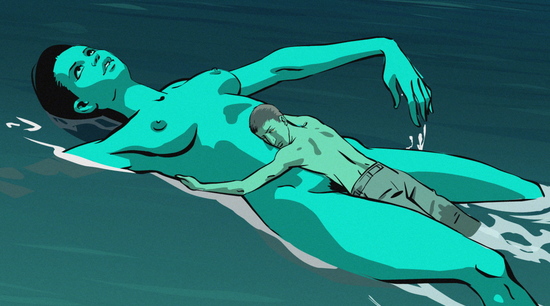

A trio of naked soldiers stride slowly through the sea past a floating corpse toward a Beirut of high-rise buildings luridly lit by orange flares. This hallucinatory image repeats like a leit motif throughout “Waltz with Bashir,” an animated documentary by Israeli Ari Folman about war and memory. At last year’s Cannes no one was busting down doors to watch a handful of Israeli soldiers reconstruct their experiences in the first Lebanon War of the early 80’s, an event barely familiar to most Americans—though the informed will recall the genocidal massacre of Palestinians that occurred in the Shatila refugee camps. Yet “Waltz with Bashir” was instantly hailed as an original, mesmerizing work that borrows the style of underground comics to explore the intersection of dream and historic fact.

Once you get the reference, the title is a gut punch in itself. The opening salvo: a man is pursued by a pack of ferocious dogs—reminiscent of fantagraphic novels - yet can’t identify his “crime.” In a bar one night he tells his friend Ari Folman that he suspects this recurring nightmare is linked to his military service in the first Lebanon War. The admission propels Folman, who’s needled by his own memory lapses about his army stint, on a quest to discover the truth of that period by interviewing fellow soldiers. Rather than a parade of talking heads pondering the fog of war, Folman offers a grunt’s-eye, absurdist view of combat—notably free of theorizing—that uncovers through dream logic and imagery the terrible events that haunt these soldiers. And rather than the rotoscopic wobble favored by Richard Linklater, Folman offers hand-drawn portraits that render his subjects uncannily vivid. “Waltz” is trippy, appalling, sexy, funny, wary of neat conclusions, and unlike anything you’ve seen.

indieWIRE: Did you always intend to do “Waltz with Bashir” as an animated documentary?

Ari Folman: Yes. I had the basic idea for the film for several years, but I was not happy to do it in real life video. How would that have looked like? A middle-aged man being interviewed about events that happened 25 years ago - and without any archival footage? SO BORING! But if it could be done in animation with fantastic drawings, it would capture the surreal aspect of war. If you look at all the elements in the film - memory, lost memory, dreams, the subconscious, hallucinations, drugs, youth, lost youth - the only way to combine all those things in one storyline was drawings and animation. You know, the question most frequently asked since Cannes is “why animation?” And it’s a question that’s absurd to me. I mean, how else could it have been done?

indieWIRE: In the film you seem to conflate war and masculinity, as if war were a proving ground for Israeli soldiers. In fact, I was reminded of how Eytan Fox tweaks the image of the macho Israeli.

AD: It’s much more complicated than just masculinity. A lot of war - when you’re really young—has to do with proving that you’re more of a man, what do you think? It’s not for ideological reasons that people go to fight. Men go to war usually for the wrong reasons—the wrong ideological reasons as well.

iW: For the character named Carmi war seems to have erotic overtones. He hasn’t had much success with women—

AF: Oh, he does now.

iW:—and then gets on a battle ship he calls “the love boat” and dreams he’s floating in the sea on top of a giant naked woman.

AF: [“Waltz”] is a very erotic film. I got some extreme reactions to it from one journalist in France. It was embarrassing, a really disturbing interview ...

iW: Do you think it’s mainly women who react that way?

AF: I can tell you that it appealed to a lot of women in Israel. They said it was the first war movie - at least in Israeli cinema—in which they could understand the meaning of war. Partly it’s the design that contributes to the erotic quality. The drawings, colors, the characters - everything.

iW: How does the design add to the erotic quality of the film?

AF: Look at the motion. People don’t walk in reality like they walk in this film. It’s a different kind of walk we developed, slow and awkward. We had problems in animation creating this slow movement. It’s much easier to make action scenes. So we decided to turn the problem into an advantage. The repeating scene in the water is sexy because it’s not a realistic style of movement.

iW: Is sexiness a bit incongruous in a film about a mission ending in a massacre?

AF: To tell you the truth, the erotic was not something that was intended, it just happened in the making of the film. War is a lot of terrible things. It can be like a really bad acid trip. You think, It can’t go on any longer, and then it does. I wanted to give that feeling in the film. And the vicious dogs at the beginning get you right into that kind of language.

iW: Why include that scene from a porno movie?

AF: The most common shared memory of people who came back from Lebanon was it was the first time we ever saw porn. We didn’t have VCR’s in Israel in 1982 - not until 1984. The army invaded a different country and in each house there were VCRs and movies on big cassettes. A lot of people told me, yeah, it was the first time for me to see a porn movie, so I thought I should include it. We had a censored version of the porn scene for the U.S. but these guys here [at Sony Classics] decided not to use that version. The censored version is funnier. Remember that Mark Spitz speedo with stars and stripes? We put stars and stripes on everyone in the porn scene, including the dog.

iW: Can you describe the animation process used in the film?

AF: “Waltz with Bashir” was made first as a real video based on a 90-page script. It was then made into a story board, and drawn with 2300 illustrations that were turned into animation. The animation format is a combination of Flash animation, classic animation and 3D. I want to emphasize that this film was not made by rotoscope animation, meaning that we did not paint over the real video. We drew it again from scratch with the great talent of art director David Polonsky and his three assistants.

iW: You’ve said you were not influenced by the rotoscope animation of Richard Linklater. So what were your models?

AF: Graphic novels - not something like “Persepolis,” but Joe Sacco, Jason Lutes, Chris Ware.

iW: How did your experience making documentaries for TV prepare you for “Waltz?”

AF: I made an experiment in my documentary TV series “The Material That Love is Made Of.” Each episode opened with a three-minute animated scene introducing scientists talking about the “science of LOVE.” It was basic Flash animation. It worked so well that I knew a feature length animated documentary would eventually work. I think you get enormous freedom with animation and illustrations. It’s a really great language for me, the best. You can imagine everything. It can be done if you have the right people, with their own perspective on things. Illustrators are brilliant.

iW: Much in “Waltz with Bashir” is deeply personal, yet it appeals to people very broadly. Do you have a theory about why?

AF: I think that in general it tells you about repression (of memory). And that has universal resonance. Everyone has gone through some event in life that they chose deliberately to forget. It doesn’t have to be such an extreme event as war, it could be a broken heart, a loss of family when you were young. You could go down in the street and choose anyone at random, and something occurred to him in life, and he decided, I don’t want to deal with it, I’ll just go on. Which is probably good.

: You’ve said you were not influenced by the rotoscope animation of Richard Linklater. So what were your models?

AF: Graphic novels - not something like “Persepolis,” but Joe Sacco, Jason Lutes, Chris Ware.

iW: How did your experience making documentaries for TV prepare you for “Waltz?”

AF: I made an experiment in my documentary TV series “The Material That Love is Made Of.” Each episode opened with a three-minute animated scene introducing scientists talking about the “science of LOVE.” It was basic Flash animation. It worked so well that I knew a feature length animated documentary would eventually work. I think you get enormous freedom with animation and illustrations. It’s a really great language for me, the best. You can imagine everything. It can be done if you have the right people, with their own perspective on things. Illustrators are brilliant.

iW: Much in “Waltz with Bashir” is deeply personal, yet it appeals to people very broadly. Do you have a theory about why?

AF: I think that in general it tells you about repression (of memory). And that has universal resonance. Everyone has gone through some event in life that they chose deliberately to forget. It doesn’t have to be such an extreme event as war, it could be a broken heart, a loss of family when you were young. You could go down in the street and choose anyone at random, and something occurred to him in life, and he decided, I don’t want to deal with it, I’ll just go on. Which is probably good.

iW: I’ve seen your film twice and would go back a third time just for the sound track. You use classical music at unexpected moments.

AF: Yes, the Bach Piano Concerto # 5 repeats three times. And the Schubert sonata opus 959 is transformed into different styles - and plays over the whole ending [live archival footage revealing the Shatila massacre]. Then Max [Richter, a German-born Brit composer] made some electro Schubert for the ending titles. Max writes a combo of classic and electronic music, and performs on a computer with a band and strings. It’s pretty cool. He’s totally responsible for the music. One song written specially for the film is called “Good Morning Lebanon.” In the opening scene with the dogs it’s techno, electronic music.

iW: And in the scene on the tanks, when the soliders are firing away, you use a sonic background sound to manipulate - in the good sense - the viewer.

AD: It’s the back sound of the film all the time. They invented that sound in the studios, they went in search of it. Putting in the sound is the best part, you’re just having fun. We did the mixing in a studio in Berlin that used to be the gym of the Nazi leadership. The foyer was donated by Mussolini. The building and sound facilities were incredible. I was there for six weeks with all these talented German guys and a guy I brought from Tel Aviv. In the dog scene we had 98 tracks that we reduced to 5 tracks on a big mixing console.

iW: Why did the Israeli Left object to the film?

AF: Because they thought it didn’t place enough national blame for the massacre.

iW: Well, why didn’t you hold the leadership more to account? Sharon was complicit, after all, he allowed the massacre to happen.

AF: I didn’t want to make any statement about the leadership. I wanted to recreate the world of the ordinary soldier. There was a commission that found Sharon guilty, he was banned from office for life, then he came back as Prime Minister, came back as a hero, think of it. Those things happen in Israel ... Bottom line, for me it was not a revenge film against Ariel Sharon. As for why he didn’t stop the massacre, he’s asleep now, so we can’t ask him. The whole plan for Lebanon was so sick, to my mind. What the master plan was nobody really knows.

iW: Rather than presenting an argument, this film unfolds with dream logic. How did you structure it?

AF: I’m always on the verge between reality and fantasy and dreams in whatever I do.

iW: You mean, right now, just sitting here?

AF: Yep, but especially when I write. This borderline between reality and dream really blows my mind. For me it’s natural. That’s why animation is so natural for me, you can go from one dimension to another. This film has a very strong structure in the screenplay -

iW:—of a quest.

AF: Yes, and all the other elements were just supporting. But if you look at the future, probably films will change completely, even if the basic story and storytelling will stay the same.

iW: What’s your next project?

AF: I’ve optioned a novel by Stanislaw Lem, a Polish author who wrote “Solaris.” It’s called “The Futurological Congress.” It’s fiction but it’s going to have a leading American actress in it playing herself. The present will be live action, the film’s future time will be drawn.

iW: As a young draftee, you had your own demons to exorcise regarding the war in Lebabnon. Was the making of “Waltz with Bashir” therapeutic for you?

AF: I’d say the filmmaking part was good, but the therapy aspect sucked.

“Waltz With Bashir” is nominated for best foreign language film at the 81st Academy Awards

back to the top

Self-Portraits and Biopics Dominate 14th Rendez Vous With French Cinema

Jean-Francois Richet’s “Mesrine” is a bloody, hi-octane account of a legendary gangster. In “The Beaches of Agnes” Agnes Varda looks back at eighty at her own momentous life. Light years apart in spirit, the two films are part of a cluster of remarkable self-portraits and biopics that dominate the 14th edition of Rendezvous with French Cinema. Unspooling at the Walter Reade Theater and IFC Center March 5-15, this year’s edition is notable, too, for the accomplished work of women filmmakers, including Claire Denis with her glorious “35 Shots of Rum”; and for selections from auteurs Claude Chabrol (“Bellamy”), Andre Techine (“The Girl on the Train”) and Benoit Jacquot (“Villa Amalia”). As well, after a sense that recent Rendezvous were serving up too many “seconds,” as we say in the schmatte trade, it’s heartening to report that Martin Provost’s fest entry “Seraphine” just won seven Cesars, including best picture, while Jean-Francois Richet snagged best director for “Mesrine.”

Jean-Francois Richet’s “Mesrine” is a bloody, hi-octane account of a legendary gangster. In “The Beaches of Agnes” Agnes Varda looks back at eighty at her own momentous life. Light years apart in spirit, the two films are part of a cluster of remarkable self-portraits and biopics that dominate the 14th edition of Rendezvous with French Cinema. Unspooling at the Walter Reade Theater and IFC Center March 5-15, this year’s edition is notable, too, for the accomplished work of women filmmakers, including Claire Denis with her glorious “35 Shots of Rum”; and for selections from auteurs Claude Chabrol (“Bellamy”), Andre Techine (“The Girl on the Train”) and Benoit Jacquot (“Villa Amalia”). As well, after a sense that recent Rendezvous were serving up too many “seconds,” as we say in the schmatte trade, it’s heartening to report that Martin Provost’s fest entry “Seraphine” just won seven Cesars, including best picture, while Jean-Francois Richet snagged best director for “Mesrine.”

In “The Beaches of Agnes” New Wave vet Varda has contrived a wondrous vehicle for recapturing watershed moments, a kind of cine memoir that filters her past through the many beaches, from Noirmoutier in France to the Pacific in California, that in some way shaped her. Shooting in HD video, Varda includes reenactments of events in her life; old photos (she started as a photographer for Jean Vilar); excerpts from both her own films, including “Cleo from 5 to 7” and “The Vagabond,” and those of her late husband Jacques Demy. At times Varda is archly literal, as when she walks backwards or sets up mirrors on the beach that reflect and coexist with “real” water and sky. Continually inventive and playful, the film has the artisanal flavor of something made up as it goes along. So many striking moments: a cartoon cat who comically “interviews” Varda in the electronically altered voice of Chris Marker; a scene from her first film in 1954, projected on a makeshift screen on a moving wagon. And over it all a wash of ironic nostalgia, but also deep sadness. The most moving moments, which catch Varda weeping, display her photos of the beautiful dead - my God, the young Gerard Philippe! - including portraits of Jacques Demy, “le plus cheri des morts.”

The second of Rendezvous’ luminous cine memoirs - and not to be missed - is “Stella” an account by Sylvie Verheyde of her own coming of age. Stella Vlaminck (tellingly with the same initials as the filmmaker) is an 11 year old girl from a blue-collar background, living in her parents’ cafe-hotel—where, she tells us in voiceover, “guys die of cirrhosis and stuff.” Transferred to a classy secondary school, she at first flounders, then comes into her own, surmounting the marital meltdown in her family. Dispensing with Hollywood hoopla, this film approaches the triumph over adversity with an unassuming tone, layering Stella’s streetwise voice over events that tumble in on you.

“Mesrine” comes in two installments: Part 1, “L’instinct de mort,” based on a memoir by Jacques Mesrine; and Part 2, “L’ennemi Public #1,” to be released separately. This gangster epic reflects the current predilection of French filmmakers for genre flicks and commercial versus arthouse. If New Wavers Truffaut and Godard found inspiration in American cinema, well, now a fresh generation of Gallic filmmakers is again looking across the pond—Variety dubbed them “French New Wave 2.0.” (Other recent examples are “Ne le Dis a Personne” and “Roman de Gare,” which lend a French twist to Studio-type thrillers.)

Be forewarned: from its opening scene, “Mesrine” deals in arterial spray, taking violence to new, well, lows. Yet the feral energy of Vincent Cassel (who bagged a Cesar for best actor) and the film’s headlong pace make it all compulsively watchable, even when you want to look away. An early scene of Mesrine observing a violent interrogation when serving as a soldier in Algeria suggests that he was either traumatized by or schooled in the brutality he witnessed. Plus dad was a “collabo,” which didn’t help. Part 1 follows his apprenticeship to sleezy gangster Guido (Gerard Depardieu); marriage and doting fatherhood; a construction stint in Montreal, where he meets soul mate Cecile de France and they brutalize a gullible millionaire. The centerpiece is a daring prison break Mesrine orchestrates with a Canadian inmate, their motto “out or dead.” Honorable in his fashion, Mesrine attempts a risky flyby to rescue his prison cohorts, and, thanks to Cassel’s charisma, you’re rooting for the guy every second. Part 2, which I haven’t yet seen, explores Mesrine’s talent for playing the media, plotting Houdini-like escapes, and outfoxing the fuzz with ingenious disguises. It’s even bloodier, I’m told, than Part 1.

A 180-degree turn and you get Martin Provost’s Cesar-winner “Seraphine.” The fictional biopic follows the life of Seraphine de Senlis, magically embodied by Yolande Moreau, a washerwoman and maid who secretly paints hallucinatory canvases of flowers, creating pigments from soil, animal blood, and oil filched from the church. Her “guardian angel,” she claims, guides her hand when she paints. German art critic Wilhelm Uhde, a collector of Le Douanier Rousseau, accidently discovers Seraphine’s outsider or “naif” paintings and gives her a show - but she’s destabilized by her new world. Especially luminous are depictions of French rural life and the artist-mentor bond between Uhde and the painter.

Claire Denis’s “35 Shots of Rum” marks a fest high point. Alex Descas works as a train conductor and enjoys a harmonious, almost coupled life with his beautiful marriageable daughter (Mati Diop), the situation evoking Ozu’s “Late Spring.” Familial harmony is disrupted, however, by the romantic urges of a restless neighbor, Claire Denis regular Gregoire Colin. The film lays out an almost plotless story about the struggle to let go and move on, using ellipses you could, well, drive a train through. Daringly, elegantly, Denis keeps life-altering moments out of the frame. Though most of the characters are black, there’s no ghetto misery or anger, color is not the main issue. “35 Shots” is a must-see for the way it captures the texture of lived life—especially the dancing scene in a cafe, where the great DP Agnes Godard records the young couple’s rapture as only cinema can. Denis is the least literary of filmmakers, taking you where language falters.

Testifying to the broad range of current French cinema, several works in the fest reach beyond personal drama to address concerns of the larger world. Socially engaged Costa Gavras weighs in with “Eden is West,” the tale of illegal immigrant Elias (studly Riccardo Scamarcio) from some unspecified locale, who battles to gain a foothold in France. After leaping from a tanker to avoid arrest, Elias swims to shore and wakes to find himself, ironically, in luxury resort Eden Club Paradise, surrounded by nude bathers. Suddenly the story takes on a Candide-like allure, as Elias disguises himself as an attendant, gets groped by a club official and pulled into the bed of a lady from Hamburg. The barbarity of the Haves - a club activity involves hunting down les clandestins with dogs and baseball bats - contrasts with the kindness of fellow pariahs, along with women, who are drawn to Elias’s hunky looks. A ride with two weirdo truckers, a stint in a factory, countless flights from the police, and Elias finally makes it to Paris. Though a picaresque string of incidents, the film generates sympathy for this hunted, embattled figure, about as welcome in Eden as a cockroach.

Pierre Schoeller’s “Versailles” also looks at the marginalized: a homeless woman and her son, who fall in with a squatter, the late Guillaume Depardieu, living in the shadow of France’s great symbol of opulence. After bonding with the boy - temporarily dumped by his mother—the homeless man manages to set him on the good path. This inspirational story is relayed without an iota of sentimentality. How wrenching to watch Depardieu, a strikingly beautiful man and mesmerizing actor, who after a history of drug problems, recently died of pneumonia at age thirty-seven.